Author Archives: Hazzan Jesse Holzer

Cantors Assembly Solidarity Mission Day 4 & Closing thoughts

Day 4 and Concluding reflections

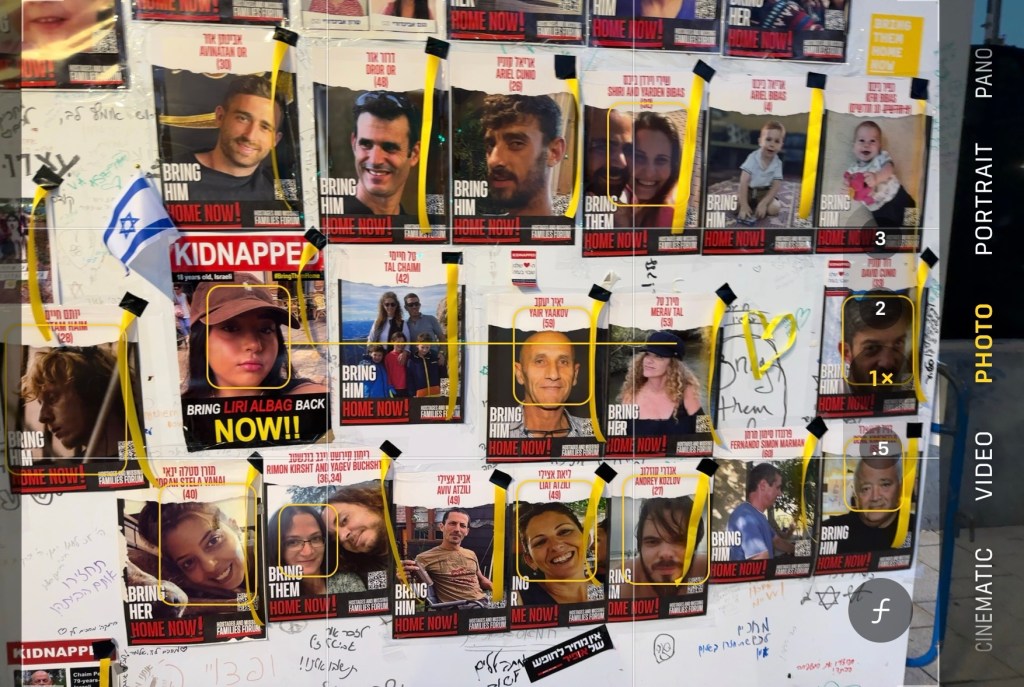

The remainder of our last day in Israel focuses on the hostages and their families. First, we visit the Hostage and Missing Families Forum, known through the hashtag #BringThemHomeNow. According to their website, the Hostage and Missing Families Forum was formed by the families of the abductees less than 24 hours after the horrific attack by Hamas on Israel on October 7th, in which more than 1300 innocent civilians were murdered and hundreds were taken hostage. The Forum is volunteer-based and laser-focused on bringing the hostages back home to their families, to us.

Our guide Meirav reiterates the volunteer nature of this NGO as people work around the clock in addition to, in many cases, full time jobs. The two goals are to keep the return of the hostages in the forefront of the political agenda as well as supporting the families of the hostages. We meet members of a number of the teams- the diplomatic team mobilizes awareness in their own governments, the medical team provides mental health resources for families and supplies medical info of the hostages to the Red Cross, whom Meirav describes as acting like a GETT taxi driver, refusing to offer medical attention when needed; the legal department, communication department (think of all the billboards in 90 locations around the world); the social media team who write everything in Hebrew AND in English; and the influencer department, where we learn from Brian Spivak (originally from Englewood, NJ) who works with creators and influencers to share stories about the hostages- one such example is the “recipes4return” campaign on Instagram where food bloggers make recipes while sharing stories of the hostages. We learn that the color scheme of the posters, often in the jarring black, white and red colors, now includes a yellow ribbon inspired by the yellow ribbon campaign for veterans, here in the US.

After the terrors of October 7, Dudi Zalmanovich, a prominent Israeli businessman whose daughter survived the massacre at the Nova festival and whose nephew was taken captive by Hamas, emptied two floors of his office and gave birth to the forum. We hear Dudi speak about the days immediately after and how the forum is adapting to the reality of some hostages being released. A number of times, he says that doesn’t matter Israeli or non-Israeli, Jewish or not Jewish, they want all of the hostages home safely and home speedily. After we sing a very emotional Acheinu (a literal prayer for hostages) in our little hallway, Dudi’s statements come into play in real time, as a family member receives a phone call right next to us that Aisha Ziyadne, from the Bedouin community of Ziyadne, is one of the captives being released (if you’re thinking Bedouin – a reminder that Hamas doesn’t want people of all religions living on this land). Later that night, we learn that her brother Bilal is also released. After an embrace, As Dudi puts it, “to see this person so drained yesterday and now today…” Even in the joy of the moment, the shirt he wears reminds us that there are still other family members in captivity.

After picking up posters and t shirts to bring back to the states, we make our way to what has been renamed Hostage Square. I’ll let the images speak for themselves, as artists and family members find a way to express their sorrow, their pain, and their hope, all in one instant. I think of the end stages of life: this is a hospital visit, shiva home, and living monument all wrapped into one. Just as in a shiva home, we are told not to start asking questions or talking too much when we interact with families of the hostages gathered in the tents. If they want to talk, they will initiate. I listen in on a conversation with the aunt and uncle of hostage, Elkana Bohbot. With everything going on, life being a blur and in many ways halting on October 7, it was comforting for me to hear the two of them laugh with friends, even for a short moment. Normalcy is something we all crave.

Everyday at 5pm, community members gather in the square for prayers and shira b’tzibbur, communal singing. We were privileged to help lead this ceremony, with our instruments, our voices, and our fullest kavanah. More than singing at the hospitals (often singing “to” the families), this was a spiritual communal moment when everyone was singing. It was nice to see our Masorti counterparts and other friends visiting from North America.

Our final dinner at an amazing restaurant, Goshen (photos included), was a way to express gratitude to our guide Kari, our producer Ben, videographer Or and all of our colleagues for experiencing the power and difficulty of this mission, together. As we shared words around our table, it also helped me to begin to formulate the narrative that I hope to share with all who read.

As I write this last post, the mood is changing in Israel. Hamas breaks the ceasefire by firing into Israel, by not sending a new list of hostages to be released. Yes, the 7 day ceasefire that saw over 100 hostages released, that had enveloped our entire 5 day journey, is over. It makes this experience unique, an ענין של זמן , a moment in time.

As the psalmist writes in psalm 121,” the guardian of Israel neither slumbers nor sleeps.” Israelis, the literal guardians of Israel, neither slumber or sleep. The resilience of this country is unbelievable- believe the unbelievable, as I mentioned early, can be a positive too. I pray that there are pockets of relief, followed by blankets of joy in the days ahead. While this is an indictment of Israel’s government, the intestinal fortitude of each Israeli to push on, to have open hands and hearts to family and strangers, is something we on this side of the Atlantic can learn a lot from. Israel mobilized, and we CAN do the same- for our own communities and for the state of Israel.

In the complexity of sadness & joy in every moment, an image is engrained in my mind- that of the tall Cedar trees that we found in Tel Aviv, in Kfar Aza, in Ashkelon, in Alumim, in Jerusalem. Cedars that stand tall even in the midst of chaos. Just as we speak of the inhumanity of Hamas, we MUST speak of Israeli expressions of humanity. Facts and figures are important, but human touch points will be what is needed to change the narrative.

When our group shared those last moments of gratitude, our videographer Or (you’ll see his work soon thanks to funds we raised at the JJC), said that WE are the hope. WE, the cantors on this mission, and WE Israel’s family and friends in the diaspora. This isn’t something Israelis would’ve said two months ago…

As we often have had a shaliach (emissary) with us in Jacksonville, I’ve never felt more of a shaliach representing and strengthened by you. The messages on Facebook, and in particular a video my daughters made with their cast of Newsies (shared later), have brought me to tears when I’ve felt overwhelmed. Being in Israel, sharing music, stories and lots of hugs, has been the language that pierces the heart and soul. Together, Israel and diaspora, are the hope. Just as we can have boundless love, we can always have boundless hope- hope for the return of hostages, for peace, for a people of Israel that thrives for generations to come. Am Yisrael Chai

When a fortress is also an open tent

Parshat Vayeira begins with the following story:

God appeared to him by the terebinths of Mamre; he was sitting at the entrance of the tent as the day grew hot. (2) Looking up, he saw three figures standing near him. Seeing this, he ran from the entrance of the tent to greet them and, bowing to the ground, (3) he said, “My lords! If it pleases you, do not go on past your servant. (4) Let a little water be brought; bathe your feet and recline under the tree. (5) And let me fetch a morsel of bread that you may refresh yourselves; then go on—seeing that you have come your servant’s way.” They replied, “Do as you have said.” (6) Abraham RAN into the tent to Sarah, and said, “Quick, three seahs of choice flour! Knead and make cakes!” (7) Then Abraham ran to the herd, took a calf, tender and choice, and gave it to a servant-boy, who hastened to prepare it. (8) He took curds and milk and the calf that had been prepared and set these before them; and he waited on them under the tree as they ate.

Abraham offered morsels of bread and a little water. He returned with a feast- cakes, meat, and milk. It’s also the first example of chutzpah in the bible, as he really gets others (Sarah/servant boy) to do the bulk of the work while he does the running. Collectively, that’s the power of audacious hospitality.

The Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 127A) relays the following discussion:

Rabbi Yoḥanan said: Hospitality toward guests is as great as rising early to go to the study hall…And Rav Dimi from Neharde’a says: Hospitality toward guests is greater than rising early to the study hall…Rav Yehuda said that Rav said on a related note: Hospitality toward guests is greater than receiving the Divine Presence, as when Abraham invited his guests it is written: “And he said: Lord, if now I have found favor in Your sight, please pass not from Your servant” (Genesis 18:3). Abraham requested that God, the Divine Presence, wait for him while he tended to his guests appropriately.

Welcoming others into our tent comes first, even before welcoming God.

Looking at our own community- how can we show acts of audacious hospitality- to those we know, and those we might not know?

It was back in February of 2009, roughly 15 years ago, that our Safer Shabbaton Scholar-in-Residence was Dr. Ron Wolfson, professor at American Jewish University and author of a recently penned book entitled “The Spirituality of Welcoming: How to Transform Your Congregation into a Sacred Community.” Using his research as our guide, our board and staff at the time began exploring best practices and what might prevent us—as individuals or as a community—from being fully welcoming?

Greeter training, better signage, colorful handouts, transliteration guides, come as you are, our doors are always open… A number of great ideas came from out of this Shabbaton. Some ideas were implemented, but with the passage of time, many of them were not – staffing and budgetary constraints, or conflicting ideologies (imagine someone being interested in a Green initiative while also printing hundreds of Shabbat handouts each week) played a factor. But in reality, the world changed a few times over. The board of directors (none of whom are the same from 2009), the professional staff (only 2 remain), and even the shabbat regular crowd (most of you weren’t shabbat regulars here at the JJC in 2009), is a different makeup from 15 years ago. We are the same synagogue, but we aren’t the same group of people that filled these pews back then.

That being said, there were four events that changed the trajectory of how we welcome people into our community.

When you enter our building, you’ll notice a large “Stand with Israel” banner created in the summer of 2014, following the kidnapping and murder of three Israeli teenagers in the West Bank, leading to the 2014 Gaza War. It was in its aftermath that we began to add more security measures than ever before.

5 years ago, the brutal murder of 11 souls at Tree of Life, meant a full time security staff; more training, cameras, and other security measures. It’s the reason I wear a smart watch with SOS capabilities. This is the new normal.

2020. Covid taught us about protecting each other; we returned to worship with no shared kippah bins or shared scarves, but rather with hand sanitizer and masks; we balanced the hybrid of welcoming those in person while trying to maintain a welcoming atmosphere online (often leaving both parties wanting something different), and as we emerged from that point to recognize the concept of mitigated risk- we can never prevent everything from going wrong, but we can be more mindful of how to prevent further harm.

And almost one month ago. Israel is at war with terrorist monsters. And we are broken, scared, and uneasy.

All of this has meant that we, collectively, have had to recalibrate the art of welcoming. And for November 2023, in this moment at least (or in the moment I wrote this sermon) it seems like I am consumed with the feeling, that this is a place, this is a safe space for Am Yisrael Chai; a feeling that every Shabbat, here, is solidarity Shabbat, and that is a very welcoming feeling to me, the not so outsider of this congregation. And I want to go into that for a minute.

Back in March of this year, I led a caravan of baseball loving, Israel supporting fans to a South Florida pilgrimage- Ben’s Deli, and a World Baseball Classic game of Team Israel vs. Team Puerto Rico. As I stepped onto the shuttle bus to the stadium, wearing my kippah and a personalized Israel soccer jersey, a large blue star draped in the front, the Puerto Rico fans on the bus jokingly booed- not because of my kippah, or my Jewish heritage, but because I was the rival team in a baseball game. I thought “wow, we’ve made it- maybe things are turning around in this country.” On October 8, following the events of the previous day, I wore the jersey walking to synagogue, with pride, and without fear. By October 10th, those feelings of safety dissipated. I wear my Israel gear to the JCA, to synagogue, but nowhere else. When I went to a Pro-Israel rally downtown, I wore a baseball cap. I pray that my fear will subside, but for today, this synagogue is that haven, that refuge where I can express my Judaism fully, and safely; a place where we pray for our ancestral homeland and recognize it’s right to exist and defend itself. This is what welcoming means to me, today.

And for those who wear your blue ribbon outside of this space, who hang their Israeli flags, thank you for being brave to extend the openings of this tent to more dialogue and understanding. Last year, when buildings downtown were desecrated by projections of hate, we countered with projections of love. And I hope I’ll join you soon, maybe I’ll be ready in a month, when it’s time to inflate my dozen or so Hanukkah inflatables on my front lawn overlooking Scott Mill Road.

When we have this laser, singular focus on Israel, I don’t want to forget that our synagogue is so much more than a haven from the darkness that surrounds us. We may never construct a perfect setup that makes every person feel safe, or welcome, but as we aim for that as our goal, as we pray not only for wholeness and peace in the world but wholeness of an inclusive community, the onus is on the jew in the pew– often sermons we say we are preaching to the choir- but here, you are the choir, the conductor, the instrumentalist, and the soloist to make this happen.

I think about a story about the residents of ancient Jerusalem portrayed in the midrashic work Avot de-Rabbi Natan.

When the Temple still stood in Jerusalem, that city was the destination of pilgrims from throughout the Land of Israel at the three harvest festivals. The rabbinic storytellers of late antiquity relate that Jerusalem’s residents opened their homes for free to those visitors. “No person ever remarked to another, ‘I couldn’t find a bed to sleep on in Jerusalem.’ No person ever remarked to another, ‘Jerusalem is too small [i.e., crowded] for me to be able to stay over there’”.

We see the remarkable spirit of the people of Israel today, in our ancestral homeland, as thousands of displaced Israelis are absorbed by other communities- creating makeshift schools, community centers, homes. I read an inspiring story about a group of adults and youth from the Masorti Kibbutz Hannaton and its surrounding Palestinian and Jewish villages, who gathered yesterday morning to paint signs that read, “Good Neighbors Also in Difficult Times” in both Hebrew and Arabic. They hung them on the main roads in the area and at the entrances to their villages. If they can have an open tent, having the courage and compassion, the knowledge and self-awareness, to honor diversity, to embrace the simple notion that we all belong here, then why can’t we do a few small steps towards the same goal?

We can be welcoming, and we can reach the next level of being inclusive. We can be welcoming, and we can make people feel a sense of belonging. How? At our synagogue, can everyone walk in and not be seen as an outsider, not be seen as exotic, not worry that they will be treated unkindly because of the color of their skin, that they and their families are seen as members of the Jewish community?

Yes these are questions that we must always be asking ourselves:

Do we greet people with questions or statements like:

- “So, how are you Jewish?”

- “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?”

- “You don’t look Jewish.”

Do we hear ourselves or others using these amongst a host of other microaggressions?

How do we welcome the convert? Those interested in conversion? The non- Ashkenazi?

I know I’m guilty at times of a number of microaggressions.

What about the questions that come our way- whether asked out loud or internally?

For Disability accessibility:

- How have you welcomed families with disabilities in the past?

- Are your facilities accessible for folks with disabilities? Is there access to the bima for those with mobility issues (i.e.: folks with a walker, cane or wheelchair)? Do you have large-print prayer books?

For Interfaith inclusion:

- Will my partner, who is not Jewish, be allowed on the bima during our child’s bar mitzvah?

- Will my partner, who is not Jewish, be a welcome addition to the synagogue during events or services that I cannot attend?

For LGBTQ Inclusion:

- Do your membership forms utilize inclusive language?

- Do you celebrate LGBTQ Jewish heroes in your religious school? Has your rabbi spoken about LGBTQ inclusion and acceptance during sermons?

For those with sensory issues: have we considered many aspects of a service that can be overstimulating for different people? Do we offer a space that’s scent free, has comfortable seating options, limits the # of attendees or encourages people to take breaks?

After Shabbat, I’ll be sharing links to a number of these sites- 18doors, URJ, Sensoryfriendly.net as a starting point to doing a little Heshbon Hanefesh, looking inward to how each of us can be more inclusive, more aware of what we say and how we act. I have no expectation that each of us will suddenly be the extroverted greeter who brings everyone into the tent, but it can mean an extra hello, a smile…I can do better, we can do better. Yes there are more questions than answers, but I hope that each of us heeds the call of Abraham from our parsha- Hineni- here I am- I don’t have the answers, but I am here, present, prepared to do the work; I am here to welcome the stranger and the estranged the newcomer and the frequent flyer; to get out of my comfort zone without feeling unsafe, to welcome an inclusive environment despite the challenges of our time. We don’t feel safe, but we can still feel the sacred obligation to welcome all into our tent. Kol Yisrael Areivim zeh Bazeh. All Jews are responsible for one another- to help build, bond, and belong to one sacred community. Shabbat Shalom Umevorach- may we all enjoy a shabbat of peace and blessing.

https://www.sensoryfriendly.net/how-to-make-your-synagogue-sensory-friendly/

https://urj.org/blog/welcoming-vs-belonging-key-step-making-our-communities-diverse-and-whole

Can I get an Amen??

What if there was no sermon this Shabbat? Can I get an Amen? (Loud Amen)

Sorry to those who responded with Amen.

Deuteronomy 27 paints the following scenario:

(11) Thereupon Moses charged the people, saying: (12. After you have crossed the Jordan, the following shall stand on Mount Gerizim when the blessing for the people is spoken: Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Joseph, and Benjamin. (13) And for the curse, the following shall stand on Mount Ebal: Reuben, Gad, Asher, Zebulun, Dan, and Naphtali. (14) The Levites shall then proclaim in a loud voice to all the people of Israel:

(15) Cursed be any party who makes a sculptured or molten image, abhorred by יהוה, a craftsman’s handiwork, and sets it up in secret.—And all the people shall respond, AMEN (16) Cursed be the one who insults father or mother.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (17) Cursed be the one who moves a neighbor’s landmark.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (18) Cursed be the one who misdirects a blind person who is underway.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (19) Cursed be the one who subverts the rights of the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (20) Cursed be the [man] who lies with his father’s wife, for he has removed his father’s garment.. —And all the people shall say, AMEN. (21) Cursed be the one who lies with any beast.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (22) Cursed be the [man] who lies with his sister, whether daughter of his father or of his mother.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (23) Cursed be the [man] who lies with his mother-in-law.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (24) Cursed be the one who strikes down a fellow [Israelite] in secret.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (25) Cursed be the one who accepts a bribe in the case of the murder of an innocent person.—And all the people shall say, AMEN. (26) Cursed be whoever will not uphold the terms of this Teaching and observe them.—And all the people shall say, AMEN.

Before 92,003 attendended a Nebraska womens’ volleyball game or 109,318 attended a Michigan Wolverines football game, this was the ultimate crowd event, a great moment of theater. In this corner…Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Joseph, and Benjamin…and in this corner Reuben, Gad, Asher, Zebulun, Dan, and Naphtali.

This is one of two sections in the torah that we call “the curses,” but when you hear it recited out lout, it really could be called the “amens.”

So as luck would have it, in thinking about the power of amens, and in figuring out this sermon yesterday afternoon, I luckily had a fantastic teaching from Rabbi Elie Kaunfer of Yeshivat Hadar in my email inbox from just a few days ago. We love Hadar’s weekly Dvash Parsha magazine , so why not utilize their torah teachings for this week’s portion. So I thank Rabbi Kaunfer in advance for taking over the next few paragraphs:

The use of “amen” in our parashah lays the groundwork for meaning #1: accepting the consequences of a statement. In Parashat Ki Tavo, Israel is accepting upon themselves the consequence of not following various laws (being cursed). R. Yosi bar R. Hanina, therefore derives from this scene in the Torah that one general function of reciting Amen is kabbalat devarim, accepting the consequences of a statement.

The word amen has two other meanings in prayer, beyond acceptance of a consequence. Meaning #2 is to express agreement about something that has happened or is currently the case. In this way, amen is similar to emet, meaning: I affirm what was said is true. Meaning #3 is to express belief in something that will happen, but has not yet come to fruition. This is also a form of request: I hope that this will happen. Here, the tradition that amen (אמן ( is an acronym for the statement: “אמן נ לך מ ל -א – God the king is trustworthy,” and will act in the future, is particularly resonant.

But the word “amen” is not limited to its meanings: it also has a role and function in ritual performance. The Mishnah describes the performative element of the amens in Parashat Ki Tavo: Mishnah Sotah 7:5

They turned their faces to Mount Gerizim, and [the Levites] opened with a blessing… and both groups of Israelites [standing on both mountains] answered “amen.” Then they turned their faces to Mount Eval, and [the Levites] opened with a curse… and both groups of Israelites answered “amen,” until they had finished [reciting and responding to] the blessings and curses. (Note that the Mishnah assumes all the Israelites said “amen” to the blessings, not just the curses, even though in the Torah itself amen is only explicitly recited in response to the curses.)

This is a moment of deep symbolism, in which one mountain (Gerizim) represents the potential blessings, while the other mountain (Eval) represents the potential curses. When the Levites face each mountain in turn, they are directing their focus to the blessing or curse embodied. The people on the mountains provide the ritual response of the blessing or curse with their response of “amen.” The “amen” recited by the people, over and over again, is not only an indication of their acceptance; it is also a public ritual that elevates the moment. Imagine the power of hearing amen again and again, recited by the entire people, at each stipulation of the covenant. It is a powerful image of a group of people focused on words and responding with agreement and acceptance.

This is the power of Amen:

Talmud Bavli discusses the importance of “Amen” in tractate Berakhot 53b:

R. Yose said: Greater is the person who answers “amen” than the person who recites the blessing. R. Nehorai said to him: By heaven this is so! Know that this is true, as the military assistants descend to the battlefield and initiate the war, but then the military heroes descend and prevail.. Aer R. Yose claims that the one who recites “amen” is greater than the one who triggered the recitation with a blessing, R. Nehorai attempts to explain this with a parable: the one who recites the blessing is simply preparing the way for victory. It is not until the appearance of those who recite amen that victory is assured”

Thus begins the origin story of the phrase, “Can I get an amen?” Blessings, even curses are a contract between the one blessing and the one hearing the blessing. There is no given that an amen will come your way. As we think of our bar mitzvah this morning- many of the major moments of Bar Mitzvah- the torah blessing, the haftarah blessing, are moments in which the kehillah, the congregation, responds verifying the eligibility of said blesser and affirming that they can be that shaliach, that emissary for all of us in the giving of the blessing.

Last Shabbat, our city was in the national spotlight following the brutal murder of Angela Michelle Carr, Jerrald Gallion, and Anolt Joseph Laguerre Jr by a racist white supremacist, radicalized by hateful rhetoric.

The next day, I found myself downtown for a trio of events- The first two taking place at the Jessie downtown. THe first was a meeting of Jacksonville leadership spearheaded by Rudy Jamison, Jr., who now serves as the Executive Director of the Jacksonville Human Rights Commission. Following the meeting, a program (already on the books) marked the 63rd anniversary of the Jacksonville Youth Council NAACP 1960 Sit-ins and Ax Handle Saturday The program was led by activist Rodney Lawrence Hurst Sr and attended by our Mayor, the first time a mayor of Jacksonville attended such a commemoration in, well, 63 years. And finally a prayer vigil organized by Councilwoman Ju’coby Pitman and our Mayor. The bulk of the vigil, attended by New Town residents, members of the Jewish community, elected officials and more, was a place where many came to grieve, to share their frustrations, to pray. In fact, it was noted that before the 15 or so clergy spoke, they were told to “pray, not preach” for two minutes each. And throughout all these experiences, I listened. Yes, I heard anger, I heard “Jesus” mentioned once or twice, but I also heard “Amen” or rather “Can I get an Amen” throughout each prayer offered. And speaking in the vernacular and in the language of prayer, the “Amens” stood out. Those who offered an “Amen” knew what they were Amen-ing. And even if I as a Jew wasn’t always ready to Amen every blessing offered, I understood the blessing being offered, the power that the collective held in offering a congregational “Amen” and the power of those who offered prayer as a vehicle for change.

And I thought to myself:

How can we as individuals, as a collective, be better equipped to offer “Amen,” as Rabbi Lubliner often says at the end of a service with a Bar/Bat Mitzvah, a “heartfelt amen”? As outlined before, Amen means a number of things:

Amen means understanding; literally. To know what we are Amen-ing

Author and Liturgist Rabbi Lawrence Kushner, in an interview with Rabbi Mike Comins, author of “Making Prayer Real” explains the following:

I hear people say Hebrew is a barrier, or it’s not welcoming, and I say phooey! A book isn’t welcoming or not welcoming; a group of people are welcoming or not welcoming. In my former congregation in suburban Boston, we prayed the same service every week at the same time for thirty years and people came to know the whole service by heart. We have a lot of data from over fifteen hundred years that’s incontrovertible: the more you pray, the more likely you are to pray in Hebrew.

On the scale of linguistic difficulty from one to ten, of which Finnish or Turkish is a ten, and pig latin is a one, English is a seven and Hebrew is a three. There are five times more words in the English dictionary than the Hebrew dictionary. Once you get over the hump of the funny letters going in the other direction, you’ve got an easy language on your hands. And I think what rabbis Ought to say is, “Cut the complaining and learn the fricking language already.”

His words, not mine. But a friendly reminder that the great sage Rabbi Akiva started learning at age 40. And even if you don’t plan to learn a liturgy class at an Israeli university in 6 months time, how about learning about the structure of our tefillot, how about learning the meaning behind the blessings that precede the Amens, so that they become more meaningful affirmations – not only to you, but to the one reciting the brakha.

Amen means active listening. Amen means showing up. If we aren’t there- in synagogues or the holy and ordinary places that our brothers and sisters offer prayer, how can we give an Amen? If we don’t show up for one another at all times- (because all times warrant blessing- the times filled with gratitude, the times marred by struggle,) how can we offer Amen??! What conversations are taking place that we aren’t coming to, or aren’t invited to, where we can offer “Amen”? What conversations should be taking place to offer “amen”?

Amen means that even if we aren’t the one talking, we are the ones confirming and sealing the deal, for the blessing is not complete until someone else recites “amen.” We, as listeners, are part of the story. So as we approach a new year, and many of us will be in this space in just two short weeks, standing and sitting, standing and sitting, Amen-ing Ad nauseam, what can we do to better Amen others- to listen, to affirm, to know? What blessings in the coming year do we offer as blessings of merit, of gratitude, and humility, so that others will affirm their collective value? Whether you sit on this side of the mountain or that side of the mountain, may this year be one of blessing for you, of health for all and an opportunity be present for the blessing of others, Amen Amen Amen.

Barbie, Brokenness & The Blessing of The Whole Story

This past week, I took a rare, sacred pilgrimage, also known as a “date night”, to Tinseltown to watch the new blockbuster movie, Barbie.

At face value, Barbie is a toy, and like one of my favorite movies of all time, Toy Story 2, there is a power to simply referencing the toys of our youth. Whether it’s Barbie or Mr. & Mrs. Potato Head, little green men, or monkeys in a barrel, toys elicited moments of nostalgia. Like a melody or a scent, they have a power to transport us to our childhood, to simpler times.

But sometimes, as outlined in Barbie, toys mean something much more. In traveling back in time, we see that the object represents a feeling: the hope, the potential of a better tomorrow; they take us to a time when we used our imaginations in a different way, when we dreamt of all that we could be. That’s the power of a single object.

For the Jewish people, we have an object, a text that represents our Jewish future by linking us to our Jewish past. Each time we read from it, the stories and teachings come alive as if we are there in the story. The Torah- all of its iterations- from the tablets to the expansion of its teachings in the Talmud, stands as a constant symbol of our history- how we used our collective imagination to dream of Jewish peoplehood and a Jewish homeland, and of our future, as a guide to Jewish living in real time. And today, we’ll talk about how we broke that one sacred object.

We can look at our Torah reading from different perspectives: chronologically within the storyline itself, where its reading falls on the Jewish calendar, and how we, today, can relate to its message.

Last week we read the 10 commandments and the Shema, the pair that serve as the basis of our ethical and theological code of living. For the Israelites of the desert, who found themselves right outside the land of Israel, they needed to hear Torah that would lay the groundwork for a successful future in the Promised Land. That’s where we are chronologically.

On the Jewish calendar, we commemorated Tisha B’av some 10 days ago, the saddest day on our calendar; a day in which both temples in Jerusalem were destroyed. For the Israelites of the Second temple, the readings of last week and today serve a different purpose. Having experienced the loss of the temples, left bereft of a spiritual home, a place where the people would bring sacrifices to mark significant moments in their lives- where would they go? What could they do? What would Judaism look like for them?

A story is relayed in Avot d’Rabbi Natan, a companion volume to Pirkei Avot, the Ethics of our Fathers.

Once, Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai left Jerusalem, and Rabbi Joshua followed after him. Rabbi Joshua saw the Holy Temple destroyed, and he lamented: ‘Woe to us, for this is destroyed—the place where all of Israel’s sins are forgiven!’” [Rabbi Yohanan] said to him: My son, do not be distressed, for we have a form of atonement just like it. And what is it? Acts of kindness, as it says, “For I desire kindness, not a well-being offering.”(HOSEA 6:6).

As the Psalmist writes (Psalm 89:3), ע֭וֹלָם חֶ֣סֶד יִבָּנֶ֑ה, the world will be built on acts of lovingkindness, which is to say, our home is in our text and its teachings. Rabbi Yohanan and his disciples (including Rabbi Joshua) would go on to establish a yeshiva in Yavneh (BT Gittin 56b), formulating a new form of Judaism in a world where we long for Jerusalem and the temple, but they are no longer the epicenter of Jewish life.

An object, the torah, the best of the best ethical teachings, can get us even through the darkest hours. But today is about a broken torah.

One of the silver linings of our modern synagogue is the ability to catch a musical moment or a word of torah from thousands of miles away- whether in real time or later on Facebook or YouTube. Over the past few years, I have found a sincere voice of Torah through the -8-12 minute sermons of Rabbi David Wolpe, Max Webb Senior Rabbi at Sinai Temple in Los Angeles. And just a year ago, David Wolpe announced his retirement after 26+ years in his congregation. He now serves, amongst other roles, as the Inaugural Rabbinic Fellow of the Anti-Defamation League. Throughout the past year, I would find myself listening to the Rabbi’s sermons as he marked his farewell tour, creating a window into his rabbinate and his congregation. His final sermon was just a few weeks ago, and you guessed it, it was about broken tablets.

Wolpe tells a story of his first ever drash/sermon at Sinai Temple, Parshat Ki Tissa, the story of Moses shattering the first set of tablets. He quotes the biblical scholar Arnold Ehrlich, who

“believed that Moses saw the calf and thought: If the Israelites worship this calf, which they created with their own hands, what will they do when they see the tablets carved by God? Surely, they will turn these tablets, which are so much more precious than the calf, into an idol! If I don’t destroy the tablets, they will commit the ultimate desecration. By smashing the tablets, Moses was making a declaration to all of Israel: Even the handiwork of God, which you might think of as inviolable, is nonetheless just another thing. It is not a God – it is a physical artifact. I am destroying it to return you to the greater truth, which is that you were not delivered from Egypt by a thing, but by an intangible, unfathomable God, no more embodied in the tablets than in the calf.”

At first glance, broken tablets are a reminder of where we went wrong, a low point for Moses and the people of Israel. It’s also a reminder of our humanity. Wolpe argues that Moses loved the people so much, he broke the tablets so they could get a redo; the Israelites would get a chance to grow as a people, make a few mistakes on the way, and ultimately be judged on other merits. Not this moment.

Wolpe points to his own evolution on why Moses broke the tablets. He points out something he never saw when he delivered that first sermon a generation ago; time and experience paint a new perspective. In this his last message to his congregation, he says that “He broke the tablets, so his heart could be whole.”

We explored our Torah from the perspective of those wandering in the desert, to those who lost their spiritual home, and now, we come to us, those who as I said earlier re-enact this story each and every time we read from the Torah. What does the story hold for us? Well today, Parshat Ekev, reconfirms that the brokenness is part of our story.

“At that point, God said to me—carve two stone tablets…and I will write upon those tablets, the words that were on the first tablets which you shattered, and put them in the Ark” (Deuteronomy 10:1-2).

From these two verses, our rabbis derive the idea that both sets of tablets, the broken and the whole, made their way into the Ark. The Israelites carried both sets, not as a reminder of the bad. In carrying the broken, they included the whole story.

The rabbis of the Talmud echo this idea that broken isn’t always bad:

Regarding the tablets, which represented the entire Torah, and Israel at that moment were apostates, as they were worshiping the calf, all the more so are they not worthy of receiving the Torah. And from where do we derive that the Holy One, Blessed be He, agreed with his reasoning? As it is stated: “The first tablets which you broke [asher shibarta]” (Exodus 34:1), and Reish Lakish said: The word asher is an allusion to the phrase: May your strength be true [yishar koḥakha] due to the fact that you broke the tablets. (Shabbat 87a)

Every time someone returns from an honor, we offer a “yasher koach.” One may find it ironic that we say “yasher kokacha”, a reference to breaking the tablets, to someone who has upheld torah, but the Ashkenazi greeting makes a lot of sense. Each of us, human, is a keeper of Torah. There are moments when we feel broken, and moments when we feel whole. We live in both realities, often at the same time- we can love and not stand our kids, love our jobs while not liking them all the time; we make mistakes even if we strive for perfection. The greeting “may your strength be true” is symbolic of the ark that each of us holds, filled with the broken and the whole; the “broken” as much a part of us as the whole. That’s what life experience offers us.

Parshat Ekev reminds us that ideas live forever; the temple, the scrolls, humans not so much. And when we feel broken, as if the point of our journey is to be repaired, we’re reminded that life is a journey towards wholeness, marked by the experiences, good and bad, happy and sad, that make up our existence. No shame attached. As humans, the “brokenness” we feel is a core, sacred chapter of our Torah, a story that will far outlive our place in this world. We are co-authors in its ongoing writing. If we continue to play a role, then it’s our story that lives on in perpetuity. We find purpose in knowing it’s our life experience that can partner with our tradition, looking back and building forward towards a real, lived Torah. May we all find a place for the broken, the real, the raw, the whole Torah that is in each of us.

Unconditional love: with all our hearts, our souls and our might!

A little more than 15 years ago, my fiance asked if I was going to cry at our wedding. I explained that all she had to do was put a television behind her playing the final scenes of the movie “Rudy” starring Sean Astin, and I’d be a goner. Needless to say, that didn’t happen, and while I’m not a “cryer” at many things, I have become one to choke up while watching sappy movies, tv shows, or reading about inspirational stories of hope and perseverance. But what really gets me to the point of tears are the moments when I read bedtime stories to my children. And no story gets me EVERY time like Robert Munsch’s I’ll Love You Forever.

“I’ll love you forever,

I’ll like you for always,

as long as I’m living,

my baby you’ll be.”

A mother starts singing this song to her son when he’s a baby, and then the story follows him through all the stages of his life. At every step of the way, his mother is there, singing him to sleep with their special song — even after he’s married, moved out, and has kids of his own. In a full circle moment, the son holds his mother in his arms:

“I’ll love you forever,

I’ll like you for always,

as long as I’m living,

my baby you’ll be.”

But before “Love You Forever” was a nursery staple, it was a simple, four-line song too painful to sing out loud. Robert Munsch would sing silently to himself after his wife gave birth to a stillborn baby. It was the second stillbirth the couple had to mourn.

For a long time, he couldn’t even share it with his wife.

“[The song] was my way of crying,” Munsch told The Huffington Post. Munsch often performed his material in front of crowds before writing anything down. One day, the song was in the back of his mind while he was performing at a theater. He made up a story to accompany the song on the spot, and just like that, “Love You Forever” poured out on stage.

The song, and the story, were a source of comfort amidst loss. The book became a best seller for people of all ages, in all stages of life; a tribute to the unending love of parents to their children.

This is the promise we make to our children- proclaiming that until our last breath, we will be there for them- physically and emotionally; with all our hearts, with all our souls, with all our might; unadulterated, unconditional love.

With all your heart with all your soul with all your might. 3 times a day we remind ourselves that we should love with every fiber of our being, and what, or rather who should we love?…God. The hope is that God, our parent, will be there for us, God’s children, a relationship steady through the storms and adversities that would derail other relationships

Medieval commentator Rashi explains “V’ahavta” AND YOU SHALL LOVE [THE LORD] — Fulfill His commands out of love, for one who acts out of love is not like one who acts out of fear. He who serves his master out of fear, if God troubles him overmuch, leaves him and goes away (Sifrei Devarim 32:1).

When you sign on to love without condition, we love even when things are tough. DOes that love always manifest as unwavering, confident, and overflowing? No. Unconditional love doesn’t mean it’s easy, or that it’s beautiful 24/7.

Professor and Researcher Brene Brown explains in a podcast on love and vulnerability:

So I have to start by debunking one of the worst myth in the world, and that is the myth that strong, lasting relationships are always 50-50. I call BS. That is not the case. Strong, lasting relationships are rarely 50-50, because life does not work that way. Strong, lasting relationships happen when your partner or friend or whoever you’re in relationship with, can pony up that 80% when you are down to 20, and that your partner also knows that when things fall apart for her, and she only has 10% to give, you can show up with your 90, even if it’s for a limited amount of time

Brown and her husband check in by telling each other their levels in terms of “energy, investment, kindness, patience.”

And what about the times when neither partner is doing well, and no one has anything to give? When Brown and her husband are both running on empty, she said they “sit down at the table anytime we have less than 100 combined and figure out a plan of kindness toward each other.” -Even that moment, -in other words, the “how do you not kill the other person?” moment, you find a relationship built on trust.

The pact we make with our loved ones is at its core a mindset; a mindset that we are doing as much as we can, lovingly; that even the most difficult moments are informed by the love that guides them.

Our V’ahavta prayer teaches a love of the divine, and in turn, a love of all who are created in God’s image. All of us. Why should unconditional love be a gift we give to an exclusive group. Is it a capacity issue- that we don’t have a full enough heart to embrace all the world’s tzuris? No, in fact Brown’s model reassures us that we DO have the capacity to love.

We are here on Shabbat Nachamu, a shabbat of comfort, a shabbat that follows our darkest hour as a people. The aftermath of the 9th of av meant we had to find other reminders of our relationship with the divine- through teaching our children, everywhere and at every moment, giving us reminders that God is still with us in the depths of despair. It is sometimes in the darkness that we see how love manifests itself, even towards a stranger.

When we gather to bury a loved one, our clergy often speak of the most selfless act one can perform hesed shel emet, an act of true lovingkindness. Burying a member of a community is an act that we do without an expectation of reward or even a simple thank you, but we do so out of obligation, and really, out of love. When there are mourners in our midst, who in Brown’s criteria are hovering over 0%, we have the capacity, collectively, to be that other 100. We do so well in honoring the dead, comforting the mourner; it’s time to think of ways we can honor the living, and comfort the struggling.

In practical terms, it means running the full range of a human decency scale- holding off on judgment when you think you’ve been wronged but don’t know the whole story; raising someone up through the act of hakarat hatov– acknowledging the good- be they a stranger, coworker, or loved one. Each act is an affirmation that we all are co creators of a future we can all be proud of. Empathy and compassion are the ingredients to move us past mere civility and into a spiritual space, a Jerusalem on high. The mourning of our temples is a “we’ve all been there” reminder to not be quick to anger, but quick to offer an open hand and an open heart.

The stresses of life are rampant…they bog each of us down and the weight, the anxiety is often overwhelming. But each of us has the capacity to be a little more decent, a little more understanding , and a little more loving. With all our collective souls and all our collective might, we’ll build a new Jerusalem of unconditional love and support, a community on high and down here on Earth.

Journey IN life

The Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma explains how social media operates using a special algorithm. Mixed in with posts, photos, videos of your friends biggest to-dos, you’ll have a litany of “other” posts. Where do those come from? Why do I see certain posts over others? Well…if you pause on a post as you scroll through, the algorithm picks up on that as a sign that you are interested in seeing similar posts.

For me, this often means a heavy dose of clips from The Office, clips of dogs dressed up as people, or clips of amazing sports feats. While the algorithm can connect to content that is dangerous and misleading, it can also (based on the parameters I’ve mentioned) lead to some truly inspiring content.

The algorithm introduced me to the work of a “serial entrepreneur”, someone who is a self described “spiritual billionaire.” His name is Jesse Itzler.

Itzler, co-owner of the Atlanta Hawks, is so much more. He rapped in the 1990s, wrote a number of team anthems including the New York Knickerbockers “Go Knicks Go,” co-founded Marquis Jet, partnered with ZICO Coconut Water and sold it to Coca-Cola, married his incredibly successful wife Sara Blakely (founder of Spanx), and wrote two New York Times best-selling books, Living with a SEAL and Living with the Monks.

Yes, In 2015, Itzler had a Navy SEAL live in his apartment and train him in the most intense conditions for 30 days – just to “shake things up” in his life. As a 55 yr old athlete, he uses fitness to better his relationships and the world. He once ran 100 miles – nonstop – to raise $1.5M for charity.

But most of his crazy journeys are communal in nature. Itzler started a race called 29029, an ode to Mt. Everest’s 29,029 ft of elevation. It’s an endurance event- a physical and mental challenge, that anyone could participate in. You don’t have to be a runner, swimmer, cyclist or “obstacle-course-type of person.” Everyone pushes everyone to the finish line. As the event website states, “overcoming obstacles reveals the best in each of us.” In May, Itzler recruited a dozen strangers to take a 2 week biking trip, some 3000 miles, from San Diego to St Augustine, raising funds for families who cannot afford cycling equipment. In both experiences, Itzler talks about the community bonds that form from being in those moments together. It’s the ultimate “bubble” experience that brings everyone who participates closer together, even for a short period, in the bonds of life.

Yes Itzler is a billionaire (in large part thanks to his wife’s empire), and he could just write a check to those charities that speak to him, but he describes himself as a “spiritual billionaire.” In an interview, Itzler explained

“that his father was never a billionaire in financial terms, but his father was the ultimate spiritual billionaire, the only currency that really matters in life. This was profoundly represented to Jesse when he was researching retirement homes for his mother after the passing of his father. The evaluation process didn’t include analysis of bank accounts, connections or social status, but was based on a retirement grading system of wellness, known as “SIPPS”–social, intellectual, physical, purposeful, and as Jesse emphasized, spiritual. Jesse explained the value of being a spiritual billionaire is the ultimate multiplier in life. One can have billions of dollars in the bank, but if they don’t have anything else of value in their life, they ultimately have nothing. In other words, being a financial billionaire multiplied by zero spiritual wealth equals zero. He encouraged everyone to spend more time on the spiritual side of the equation, as that is the true multiplier of life.”

When speaking about the legacy he’ll leave his four children, Itzler says “One of the hardest things as a parent for me is recognizing that our kids are on a different journey than us. For example, I liked to play basketball in my driveway until midnight…my sons like to play Minecraft. And that’s amazing.

That said, I’ve learned to focus on certain things that matter most regardless of what our kids decide to do: self esteem, grit, empathy and compassion. We’ve found the best way to build those qualities in our kids is to show them. They are watching.”

This is probably not the first time you’ve heard some guru advice about appreciating the journey. It actually takes place in the second half of our double parasha, Masei.

“These were the marches of the Israelites who started from the land of Egypt, troop by troop, in the charge of Moses and Aaron. Moses recorded the starting points of their various marches as directed by the Lord….” (Numbers 33:1-2).

Parashat Masei, the second of the two portions that we read this week, begins with the recounting of the Israelites’ itinerary, outlining their travels from Egypt through the desert, acting as a checklist before the “promised land moment.” I mean this is it- the end of Numbers is that threshold moment outside Israel. Deuteronomy is mostly a reprisal to get us to those final moments before we enter the land.

So the rabbis go back and forth as to why we have this listing of directions that reads more like an old printed Mapquest guide.

Approach 1: Remember the miracles; show God’s power. Each stop represents God’s miraculous moments.

Approach 2: Remind the Israelites of where they went wrong, both in the places they rebelled and in the fact that they are traveling so long in the first place.

Approach 3: The faith of the Israelites. Yes they had to walk around in circles, and they weren’t always compliant, but in the end, they maintained faith in God.

I’d like to add a fourth approach. By repeating the Israelites’ itinerary, we place value on life experience. Yes our faith wavered and remained intact, somehow, but I would argue that more importantly, we experienced all the ups and downs, the journey, together; and the bonds of that journey are everlasting friendship and community.

The journey is more than just for you– it’s for those who you take with you on the journey- family, friends, even strangers. It’s about finding that lucrative deal where one can maximize the quality AND quantity of interactions with loved ones. Which brings me to the first Jesse Itzler video to pop up on my social media feed. It’s the video that launched an algorithm of more Itzler videos. In a standard back and forth question sequence he has done in a number of interviews, Itzler asks the interviewer, Rich Roll, the following:

J: My parents are both alive. Are your parents alive?

R: Yeah

J: How older are your parents?

R: 76, 74

J: And where do they live?

R: Washington DC

J: How often do you see them?

R: like twice a year

J: Ok, so most people’d be like, “okay, you know I have…lets say your parents live until 80, so they have five more years, lets just say roughly, you would say “I have five more years of my parents” but I would say, “no, you have 10 more times with your parents if you see them twice a year.” You see them twice a year times 5, you have 10 more times to see them. WHen you start thinking of things like that, your first reaction is, “I wanna go see my parents.” At least that’s mine. So you change the way you approach it, and I’m like “I’m gonna go see my parents every other month, I’m gonna make it a priority”

Many of us prepare for retirement, or prepare for our ultimate retirement, our death. We do so in the hope that we have a financial portfolio that puts our loved ones at ease, thinking about the literal capital we leave for them. Rarely are we thinking in spiritual terms- we should aspire to be spiritual billionaires, leaving a legacy of a journey well taken. And while we can sometimes have a clearer picture of life as a Journey towards something- towards retirement, towards death, towards the world to come, life is really a journey IN something.

Take a moment to think about Itzler’s scenario: if you have 10 years, 20 years left on this earth, how does that equate to different journeys you might take? Is that 10-20 more times in shul? Is that a few dozen times seeing your friends for lunch? The question isn’t intended to freak you out, although I do recall kids at summer camp crying because that Tuesday was the last Tuesday french toast that they’d ever have as a camper. Rather, it’s a question to motivate us to live IN the journey, to make time for meaningful moments and meaningful conversations, to engage rather than dismiss.

Rabbi Harold Kushner, of blessed memory, who guided so many on this path of life and loss as a rabbi and an author, wrote the following:

“The purpose in life is not to win. The purpose in life is to grow and to share. “When you come to look back on all that you have done in life, you will get more satisfaction from the pleasure you have brought into other people’s lives than you will from the times that you outdid and defeated them.”

At our regular healing service, I often highlight a line from one of our healing prayers that reads “we celebrate the journey, this precious gift of life.” May we celebrate our journeys, enhanced because we walk them, with purpose, together.

Our successes in life will be defined by engaging IN life, IN partnership with others, not towards something else- a journey well traveled, a life well lived.

There’s a favorite quote of mine from Ralph Waldo Emerson that summarizes this idea:

“To laugh often and much; to win the respect of intelligent people and the affection of children; to earn the appreciation of honest critics and endure the betrayal of false friends; to appreciate beauty, to find the best in others; to leave the world a bit better, whether by a healthy child, a garden, a redeemed social condition; to know even one life has breathed easier because you have lived. This is to have succeeded.”

We are all on the ultimate endurance course of life. May we help others breath easier, lift others up because we are on this journey, together.

Where our missions intersect, is where our collaboration begins

This week, Ben Frazier passed away following a 9 month battle with cancer. Ben was an award-winning civil and human rights leader — a long-time broadcast journalist who became the first Black anchor of a major news show in Jacksonville. He received the NAACP’s Rutledge H. Pearson Civil Rights Award for his advocacy and outstanding contributions to civil rights over many decades. He founded the Northside Coalition of Jacksonville to “empower, educate and organize our communities in an effort to establish greater self-sufficiency.” He had a VOICE and used it.

Growing up, I always felt that my rabbi had “a voice”- as the expression used to go, someone you could listen to read from a phone book, when those were actually a thing. He happened to give a great sermon, too. That dynamic duo shared by my rabbi and Ben — a worthwhile message and a voice to carry it — is hard to come by. What a voice!

I knew Ben peripherally, but I wish I knew him better. Dealing with health issues, he still showed up these past few years to fight for a number of issues of equity and equality. In 2016, Ben joined Rabbi Tilman and other faith leaders for a memorial service for those lost at Pulse Nightclub, echoing our hope that our city’s Human Rights Ordinance would expand to cover ALL of its citizens. This past November, a month into his cancer diagnosis, he brought Northside Coalitions members to James Weldon Johnson Park when our OneJax partners held a vigil of Unity & Hope following the desecration of our downtown spaces by antisemitic messages. It was important to him to show support for the Jewish community.

In a few days is the 17th of Tammuz, a day that commemorates the siege that led to the destruction of the holy temple in Juersalem. We are about to spend nearly a whole month speaking about the cause of that destruction, sinat chinam, useless hatred… and we see the embodiment of useless hatred right before us.

3 years ago, after the lynching of George Floyd, I quietly worked with partners in a number of local Jewish and non-Jewish organizations to create a series of learning sessions. Rabbi Lubliner and I participated in a dialogue series under the umbrella of Where Race Meets Religion. The Rabbi and Dr. Richard Wynn, UNF’s Chief Diversity Officer, held a forum on Intersectionality and Identity, while my session covered Allyship with Dr. Kimberly Allen, the dynamic founder of 904orward.

Ben was also supposed to be a participant. His kickoff learning session was tentatively called, “Real Talk: Encounters with Race and Racism,” but that program was canceled before major publicity was sent out.

Why? A quick Google search of the event’s co-sponsor, a national Jewish organization Bend the Arc, revealed a political campaign with overt anti-Trump sentiment, with slogans promising to “free America from [him].” At the time I wrote to our community partners: “I don’t always agree with speakers or organizations that are brought to the greater Jacksonville Jewish community, but there is a difference between not endorsing and silencing. I hope we can find ways to lift up voices and conversations in a constructive way.” But the image of the co-sponsoring organization was already tainted too much. Today, you won’t find the same rhetoric on their homepage — I can only provide conjecture as to why that is. But in name calling, in that being the focus of their message, they foolishly stopped a conversation before it could even begin, conversations that needed to happen about the fight against white supremacy, antisemitism, and racism in this country.

We said we’d have him back for a later event. Our community needed to hear his VOICE. But that ended up never happening. To be frank, Ben’s political leanings might have seemed foreign to many in our midst, and yes, part of his story is that he spoke truth, often to closed ears. But in speaking truth, in his own voice, he reached a far-ranging audience. And I wish that the Jewish community could have been more a part of his story. In a planning call for the program, Ben poignantly stated “Where our missions intersect, is where our collaboration begins.” He understood that we can’t all agree on everything, but there has to be a place where we can come together, to have a conversation.

This is the climate synagogues and synagogue professionals must operate under. Dr. Shuly Rubin Schwartz, Chancellor of JTS and our Shorstein lecturer this upcoming winter, wrote this past week, “We face an acute shortage—of rabbis, but also of educators, cantors, organizational leaders, camp staff, chaplains, youth leaders, and even lay leaders.” The shortage isn’t solely a pipeline problem, and isn’t solely one for the Jewish faith. It’s exacerbated by a mass exodus of clergy of all faiths from the professional ranks.

The Christian research organization Barna reported that in March 2022, “the percentage of pastors who have considered quitting full-time ministry within the past year sits at 42 percent”

In an article titled” Why Pastors Are Burning Out” Anglican priest

Tish Harrison Warren writes

“That the top reported reasons for clergy burnout were the same ones that people in the population at large face: stress, loneliness and political division. But these stressors affect pastors in a unique way. Pastors bear not only their own pain but also the weight of an entire community’s grief, divisions and anxieties. They are charged with the task of continuing to love and care for even those within their church who disagree with them vehemently and vocally. These past years required them to make decisions they were not prepared for that affected the health and spiritual formation of their community, and any decisions they made would likely mean that someone in their church would feel hurt or marginalized.”

The tightrope dance of speaking up on issues without alienating congregants is a top reason for clergy burnout, but avoiding the “hot topics” altogether doesn’t alleviate the stress, either.

In our torah portion, the main character, Balaam, sought to curse the Israelites, only to have God intervene as puppeteer in order to bless Israel, despite Balaam’s objections. Faith leaders, on the other hand, have the capacity, and the desire, to be facilitators of difficult discussions; to have freedom of the pulpit because they have the trust of a congregation to speak from a religious perspective that is authentic, thought-out and thought provoking. Theirs are the mouths open not in curse but in conversation.

This isn’t the first sermon on civil discourse, but I do think it helps to remind us all that there is a space in this ohel (tent), in this mishkan (portable sanctuary)- on Saturday morning, in adult education classes, in print, to have meaningful conversations about reproductive health, Israel, and gun control.

Balaam famously blesses the people of Israel:

“Mah tovu ohelecha yYaakov, mishkinotekha Yisrael.”

How good are your tents Jacob, your dwelling places Israel?

The rabbis asked why the doubling of the language? Why not say “How good your tents Jacob” OR “how good your dwelling places Israel?”

The Gemara asks in Bava Batra 60a:

From where are these matters, i.e., that one may not open an en-trance opposite another entrance, or a window opposite another window, derived? Rabbi Yoḥanan says that the verse states: “And Balaam lifted up his eyes, and he saw Israel dwelling tribe by tribe; and the spirit of God came upon him” (Numbers 24:2). The Gemara explains: What was it that Balaam saw that so inspired him? He saw that the entrances of their tents were not aligned with each other, ensuring that each family enjoyed a measure of privacy.

Our dwelling place, our synagogue, is also a tent- open to difficult conversations, open to all; but our rabbis remind us that there is room for each of us to have our own space; we can all dwell together even in our measure of privacy.

So what does meaningful dialogue look like? Can we find a way to hear people’s voices? And is there a point and place when and where we can rally around each other beyond our mutual disdain for Nazis and antisemitism?

Philosopher Martin Buber, writing in Tales of the Hasidim: Early Masters, says:

“There is genuine dialogue – no matter whether spoken or silent – where each of the participants really has in mind the other or others in their present and particular being and turns to them with the intention of establishing a living mutual relation between himself and them.

There is technical dialogue, which is prompted solely by the need of objective understanding.

And there is monologue disguised as dialogue, in which two or men, meeting in space, speak each with himself in strangely tortuous and circuitous ways and yet imagine they have escaped the torment of being thrown back on their own resources”

Let us aim for genuine dialogue. For while our synagogue is a misgav, a haven, a safety net from the noise and chaos of the outside world, it is also a mishkan, a place to dwell- to sit with difficult topics and sit in conversation with one another; to challenge ourselves; to grow.

To paraphrase Ben Frazier’s words, “Where our mishkans, our missions intersect, this is where our collaboration begins.” May we collaborate on a mishkan, a portable sanctuary we take wherever we go, a sanctuary built on trust, respect, curiosity and love. May we have faith in our leaders to guide us, and in our own potential to better ourselves and this world. Mah tovu – how good is the tent we can build, all of us, together?

Yizkor- Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, Something of You

At a Jewish wedding, we greet everyone, from the bride and groom to the C list guest with the greeting, “Mazal tov!” So today, in addition to Shabbat Shalom, Chag Sameach, and Gut Yuntif, today, Shavuot, our wedding day to torah and to God, I greet all of you with a heartfelt “Mazal tov!”

There’s a rhyme you may have heard from the wedding day, that brides should wear (or carry) “something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue.” It’s actually a great guide for most of our traditions to maintain meaning over time. Most of our rituals have elements of old, new, borrowed and, well, blue…

Something old:

The roots of Yizkor are found in the Midrash Tanchuma of the 8th or 9th century. In its section on parashat Ha’azinu, Moses’ swan song, it cites Deuteronomy 21:8, “Atone for Your people, Israel, whom You have redeemed.” We are told that the first part of the verse refers to the living of Israel, while the second part refers to the deceased. The Midrash continues, “Therefore, our practice is to remember the deceased on Yom Kippur by pledging charity on their behalf.” We are then told not to think that charity no longer helps the departed. Rather, when one pledges charity on the deceased’s behalf, he ascends as quickly as an arrow shot from a bow.

Yizkor was extended from Yom Kippur alone to the three Festivals, which is thematically appropriate. The Torah tells us (Deuteronomy 16:16-17) that when we make our pilgrimage to the Temple for the holidays, we are not to appear empty-handed. Each person was to make a donation according to his ability. We see from this that charity is also an integral part of the Festivals and therefore a fitting occasion for Yizkor with its emphasis on charity as a merit for the departed.

Yizkor extended beyond this idea of offering tzedaka when it added a commemoration for the Jewish martyrs slain during the First and Second Crusades. A special prayer, Av HaRahamim (Ancestor of Mercies), probably composed as a eulogy for communities destroyed in the Crusades of 1096, is often still recited by the congregation as a memorial for all Jewish martyrs.

Something blue– this wedding tradition originated as a way to ward off the evil eye. We have that in our Yizkor service as well, as a powerful superstition pervades the community: If your parents were alive, you didn’t stay for Yizkor. God forbid, you should tempt the ayin ha-ra, the evil eye, by hearing and seeing others mourn for their departed. This came into play primarily for the section of the yizkor prayers in which individuals read silently recalling the deceased. There are paragraphs for a father, mother, husband, wife, son, daughter, other relatives and friends, and Jewish martyrs. During the service, each person reads the appropriate paragraph(s).

While the custom of leaving yizkor still exists today, the rabbis remind us that there are prayers at the end that are recited for victims of the Holocaust and other martyrs; for members of our community; these apply to all members of the congregation, not just to those who have lost close family members. Some would advise staying inside in order to recite those prayers, or to go out and return for them. Something blue- we’ll come back to this.

Something borrowed:

The custom of commemorating martyrs by reciting their names and praying for their repose was borrowed directly from the Christian Church. From the 4th century onwards it was the practice of the Church, during the celebration of the Mass, to offer a special prayer for local martyrs and deceased dignitaries, their names being read out from a diptych—that is, from two wooden boards folded together like the pages of a book.

Something new, or as I’d like to call it, something of you:

Yizkor is a very personal experience. Without you, it doesn’t exist.

As in the book May God Remember: Memory and Memorializing in Judaism—Yizkor,Rabbi Shoshana Boyd Gelfand writes:

Judaism also embraces the idea of collective memory…The assertion that we all stood during the revelation at Sinai is a profound statement that all Jews are bound together in a shared autobiographical experience.

This focus on communal memory makes the Yizkor ceremony all the more striking, for Yizkor is the one moment in the Jewish liturgical calendar when what matters is not communal but individual memory, each of us standing personally consumed by singular memories of relatives and friends who have died. Unlike a funeral or shiva, where individual memories are shared publicly to fashion a collective mosaic of the person being remembered, Yizkor provides a communal space for inward memorializing. Why is it that Judaism, a religion so fully dedicated to communal memory, makes this regular exception when it comes to Yizkor?

Yizkor works differently. It is not intended as a time to sharpen our memories, for there is no corrective of physical evidence or balance provided by others’ recollections. Instead, Yizkor encourages an evolution of our own private ongoing relationship. Each time we recite Yizkor and remember, we deepen the parts of that relationship that sustain us, while forgetting those characteristics that do not.

Instead, Yizkor encourages an evolution of our own private ongoing relationship. Each time we recite Yizkor and remember, we deepen the parts of that relationship that sustain us, while forgetting those characteristics that do not.

We all have the capacity to, and responsibility to remember.

Midrash Rabbah, Song of Songs 1:3, teaches “Our children shall be our guarantors.”

According to the Midrash, when the Jewish people stood at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah, Hashem asked for a guarantee that they would keep it. They replied, “Avoteinu orvim otanu” — “Our ancestors will be our guarantors.” When this was unacceptable, they offered, “Nevi’einu areivin lanu” — “Our prophets will be our guarantors.” This, too, Hashem did not accept. When they said “Baneinu orvim otanu” — “Our children will be our guarantors” — Hashem replied, “Indeed these are good guarantors. For their sake I will give it to you!

We are the guarantors – in continuing our collective tradition, and in perpetuating our own individual memories of those who impacted us.

It’s been a little over 3 years since Rose Goldberg z’l passed away. In addition to seeing Rose on a regular basis on Shabbat morning, I’d often see her at the funerals of friends and community members. Knowing that most of our funerals take place in the heat of the day, I’d often go over to Rose to offer a bottle of water after the service had concluded. She’d often decline the offer, but ask that we walk around to the graves of her loved ones to offer an el malei rachamim, memorial prayer. We would stop a number of times en route to the Zucker/Goldberg/Mibab section of our cemetery. “Let’s do an el malei for this person- they were a teacher”, “let’s do an el malei for this person, our clergy or ritual director” let’s do an el malei for this person, they were a mensch.” No family relation, but a 90 yr old woman, on a hot summer’s day, understood that even those not related in blood have a relationship with us, long after they are gone.

I have two living parents, a living spouse, a living sibling and living children. Yet when I recite Yizkor, I remember a lot of people. I think of blood relatives – grandparents that I knew, grandparents I didn’t know so well, a grandparent I never knew…family members taken too soon. But I also take a moment to capture images of people who sat in these pews, regulars, the Rose Goldbergs, teachers and mentors of mine, and students of mine, who are no longer here, physically. Even as the sanctuary doesn’t appear to be filled, the seats fill up as if all of those I recall are sitting here, right with us.

Biblical Historian Theodor Gaster wrote back in 1953:

To this time-honored idea the Jewish Yizkor service gives a new and arresting turn: by the very act of remembrance, oblivion and the limitations of the present are defied, death is made irrelevant, and a plane is established on which the dead do indeed meet and mingle with the living. The ceremony is transformed from a memorial of death into an affirmation of life.

Time stands still. And in that moment of silence are the sounds and sights of memory. From generations before us, an unending chain that affirms the impact of those we knew in life just as we know they continue to guide us after life. To those we remember today- may their memory and our memory of them, always serve as a blessing.

Streaming the Holocaust

Growing up, a secret society met in our home. Members included husbands or wives sneaking away from their spouses, parents shunned by their children. Individuals long forsaken by society would come to our house because they possessed one unifying character trait: they loved sweet and sour tongue. My mother prepared the dish, and as witness to this prep I no longer have the stomach for the dish. The group was known as the “lashon tov” club, meaning “the good tongue” club, a play on the prohibition to gossip, aka to speak lashon hara, or “evil tongue.”

I learned a lot about Lashon Hara as I prepared for my Bar Mitzvah, Shabbat Hagadol, Parshat Metzora. In a strange quirk of our triennial cycle, this week we “read” Tazria Metzora, but because it’s the 1st year of our cycle, we don’t actually read from Metzora itself. And our haftarah is the special haftarah for Rosh Chodesh. So while we don’t speak these words this shabbat, it’s important to hear their message.

In Parshat Metzora, we encounter a skin ailment that spreads, just as gossip spreads from person to person. Our Rabbis concluded that there are different types of gossip so I’d like to take a moment to explore 3 in particular:

Lashon hara is defined as saying something negative about a person- through face-to-face conversation or by letter, email or text. These comments are mean spirited, but true. It’s because of that mean spirit that a local rabbi has a bumper sticker that says in hebrew “Lashon Hara- Lo Mdabeir Alai.” By contrast, motzi shem ra (lit. “putting out a bad name”) – is slander or defamation. Lies. Motzi shem ra is a greater sin than lashon hara. Lies are much easier to come by. We learn this in our weekday morning tractate of study:

The letters of the word truth (emet) rest on two legs [aleph -mem -, tav – ], while the letters of the word falsehood (sheker) have only one leg [shin -, kof – , resh -]. Truthful actions stand firm; actions based on falsehoods do not. The letters of emet are far apart [the first, middle, and last in the alphabet], whereas the letters of sheker are bunched together. Truth is hard to attain, but falsehood is readily at hand. III YALKUT SHIMONI, GENESIS, 3

And finally, there are times when a person is permitted or even required to disclose information whether or not the information is disparaging. For instance, if a person’s intent in sharing negative information is for a to’elet, a positive, constructive, and beneficial purpose that may serve as a warning to prevent harm or injustice, the prohibition against lashon hara does not apply.

Speaking up and speaking out against injustice and slanderous speech is not only allowed, it’s an imperative.